Listen to the article

Listen to the session

Listen to the article

In a 2019 podcast titled In A Metal Mood, Malcolm Gladwell addresses the issue of cultural appropriation. He tells how many of the top hits of the 1950s and 60s were written and first performed by Black artists, but only became popular once recorded and “appropriated” by white performers.

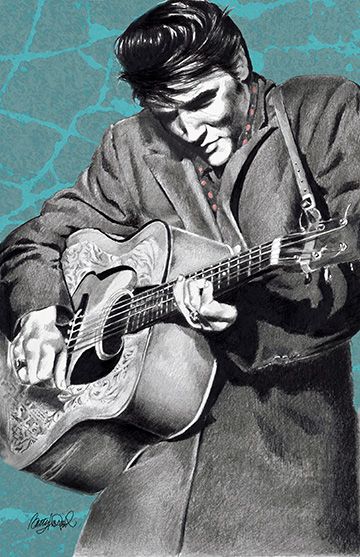

For example, Pat Boone’s first big record in 1955 was Ain’t That a Shame, written by “Fats” Domino and Dave Bartholomew. His next #1 song, Tutti Frutti, was written and first performed by Little Richard and other Black musicians. Boone’s versions, of course, were heavily toned down. Likewise, Elvis Presley’s 1956 hits Don’t Be Cruel and All Shook Up were originally written and performed by Otis Blackwell, but never gained the reach of Presley’s versions.

All of these songs—and many more—were products not only of Black writers but of Black culture. You might say Boone and Presley took the fruit while leaving the roots, which continued producing more songs for others to popularize in the years that followed. They didn’t merely cover the originals; they left audiences thinking their versions were the originals. They lifted the songs out of their cultural context and made them hits for a much wider audience. That is what cultural appropriation does: it removes something from its culture of origin, reshapes it, and claims it as one’s own—even at the cost of distorting the original.

I have been thinking about how we have done something similar with a particular passage in 2 Chronicles 7:14:

“…if my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin and heal their land.”

From the founding of our country—and especially gaining traction in the 1920s and during the Depression and then again in the 80’s—this verse has been used to organize and inspire people that there was a way out of periodic national crises. Scripture is full of “if/then” promises, but none has captured the imagination of nations quite like this one. Christians around the world have claimed it for their own countries, but perhaps nowhere is it so prominent as in America.

But is there a sense in which this too is cultural appropriation? Have we lifted the verse out of its original setting—the dedication of Solomon’s Temple—and popularized it by misapplying it?

Russell Moore writes:

“When God said to them, ‘If my people who are called by my name,’ he was specifically pointing them back to the covenant he made with their forefather Abraham. At a specific point in history, God told Abraham about his descendants, saying, ‘I will be their God’ and ‘They will be my people.’ That’s what ‘my people’ means. God reminded a people who had been exiled, enslaved, and defeated that neither a rebuilt temple nor a displaced nation could change who they were. They were God’s people and would see the future God had for them.

When we apply texts like this to the nation, apart from the story of Scripture, we do precisely what the prosperity gospel preachers do. They are drawn to passages from Deuteronomy and elsewhere that promise material and physical blessings for obedience, and curses for disobedience. The message becomes that obedience leads to wealth and health, while disobedience leads to poverty and sickness. But they misuse God’s Word by abstracting these promises from Jesus Christ. He alone is the one who, in perfect obedience, receives God’s blessing, and he alone is the one who, bearing the sins of the people, receives God’s curse (Gal. 3). To apply these promises directly to people—or to a nation—while bypassing Christ is to preach a false gospel that approaches God apart from the Mediator (1 Tim. 2:5). A prosperity gospel applied to a nation is no more biblical than a prosperity gospel applied to a person.”

There are passages of Scripture that are universally applicable. John 3:16, for instance, is for everyone regardless of nationality. But when we take a single verse with a highly specific context and generalize it, we risk not only misapplication but also leading people into the very distortion Russell warns against.

You may have seen the quip, “I can do all things through a verse taken out of context.” Let’s not do that here. Let’s not bleach out the power of God’s Word by ripping it from the people and the covenant to which it was originally given.

Get The Round Table in your Inbox

Every now and again we send out a collection of our writings, links to our webcasts, and reminders about events. Subscribe to stay in touch.